The Debt Ceiling Is A Cliff — And We Keep Raising It

The Longer We Wait, The Harder We Fall

On Friday, October 15, 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden signed legislation raising the government’s borrowing limit to $28.9 trillion. Many Americans are now accustomed to this recurring bureaucratic process and don’t think much of it or its consequences. Two sides fight, they get close to a deadline (and sometimes pass it!) and eventually raise the “debt ceiling” so they can fight over it again some months later.

We Americans, as a collective and a government, are deciding to delay paying our bills. At an individual level, we understand what happens when we don’t pay our own bills. But what happens when the most powerful nation today stops paying bills? To understand the effects of this — and how we got here in the first place — we need to study history. Let’s start with a simple short-term debt cycle.

Lending And The Short-Term Debt Cycle

The short-term debt cycle arises from lending. Entrepreneurs need capital to bring their ideas to fruition, and savers want a way to increase the value of their savings. Traditionally, banks sat in the middle, facilitating transactions between entrepreneurs and savers by aggregating savings (in the form of bank deposits) and making loans to entrepreneurs.

However, this act creates two claims on one asset: The depositor has a claim on the money they deposited, but so does the entrepreneur who receives a loan from the bank. This leads to fractional reserve banking; the bank doesn’t hold 100% of the assets that savers have deposited with it, they hold a fraction.

This system enabled lending, which is a useful tool for all parties — entrepreneurs with ideas, savers with capital, and banks coordinating the two and keeping ledgers.

Lending aids the creation of new goods and services, enabling the growth of civilization (Source).

When Times Are Good

When entrepreneurs successfully create new business ventures, loans are repaid and debts are cancelled, meaning there are no longer two claims on one asset. Everyone is happy. Savers and banks earn a return, and we have new businesses providing services to people thanks to the sweat and ingenuity of the entrepreneurs and staff.

The debt cycle in this case ends with debts being paid back.

When Times Are Bad

When Alice the entrepreneur fails at her business venture, she is unable to repay her loan. The bank now has too many claims against the assets that they have, because they were counting on Alice repaying her loan. As a result, if all depositors rush down to the bank at once to withdraw (a “run on the bank”) then some depositor(s) won’t get all of their money back.

Depositors rushing to withdraw from a bank they believe to be failing (Source).

If enough entrepreneurs fail at once, say because of an “Act of God” calamity, this can cause quite an uproar and a lot of bank runs. However, the debts are still settled, either through repayment to depositors or default, leaving depositors without their money.

The debt cycle in this case ends with some portion of debts defaulting.

The debt cycle either ends with payment or default — there is no other option. When borrowing overextends, there must be a crash. These crashes are painful but short and contained.

The Mini Depression Of 1920

The year 1920 was the single most deflationary year in American history, with wholesale prices declining almost 40%. However, all measures of a recession (not just stock prices!) rebounded by 1922, making the crash severe but short. Production declined almost 30% but returned to peak levels by October 1922.

This depression also followed the 1918–1920 Spanish Flu pandemic and came one year after the conclusion of the First World War. Despite these massive economic dislocations, the crash was short and now relegated to a footnote in history.

Finance writer and historian James Grant, founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, noted about the 1920 Depression in his 2014 book “The Forgotten Depression, 1921”:

”The essential point about the long ago downturn of 1920–1921 is that it was kind of the last demonstration of how a price mechanism works and the last governmentally unmediated business cycle downturn.”

The Free Market And Hard Money Curtail Debt Cycles

When an economy runs on a hard money system, free market forces rein in excessive borrowing and thus keep the debt cycle short.

What Is Hard Money?

Hard money is a form of money that is expensive for anyone to produce. This ensures a level playing field: Everyone has to work equally hard to gain money. Nobody can create money and spend it into the economy without incurring a cost almost equal to the value of the money itself. Gold and bitcoin are two examples of hard money, mining them requires so much time and energy that it’s almost not worth it to do so.

All those miners won’t run themselves (Source).

How Do Free Markets Rein In Borrowing?

Free market forces are crucial to limiting speculative manias. On one side, you have lenders and savers who hope to make a return on their capital, while on the other, you have borrowers hoping to take borrowed money and turn it into more money.

In a free market that utilizes hard money, there are two options to conclude the extension of credit: Debts are repaid, or debts are defaulted on. The greed of lenders wanting more return on their capital by making more loans is kept in check by the risk of default. The greed of borrowers wanting more capital is kept in check by the burden on their future self or business from increased debt.

This applies at an individual level as well: As any borrower increases their debt pile, they become riskier and riskier to lend to. That risk means lenders will demand to be paid a higher interest rate on their loan. That higher rate makes it harder for the borrower to borrow more, leading them to either turn toward paying down some of their existing debts or default outright.

These forces keep lending in balance, cutting down speculative manias before they go too far.

The Lengthening Of The Debt Cycle

Powerful entities — like governments — can use their sheer power to make them a less risky borrower.

Over the past century or so, we’ve seen many governments take on debt so that they can lend to individuals and businesses, especially during hard economic times. Those loans help individuals and businesses pay their bills and debts, easing the pain of a crash. However, this lending by governments does not resolve debts; it simply transfers debt from private individuals to the government, putting it in a large pile of public debt.

That debt didn’t disappear (Source).

Governments can build such a huge pile of debt because lenders know that a government has special tools for paying back that debt. You and I may not be able to seize the property of others in order to pay our debts, but a government can. Even the bastion of the free world, the United States, seized the privately held gold of its citizens in order to keep itself afloat in 1933.

This government debt issuance leads to a lengthening of the debt cycle. The depth of each drop is tempered, but the unwinding of debts is not completed — it is only delayed. Frequent short and sharp downturns are transformed into longer cycles with infrequent but devastating collapses.

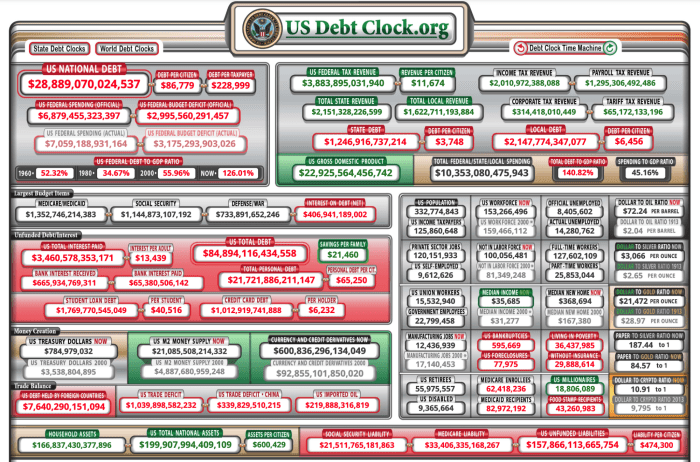

This brings us back to the debt ceiling: The reason our politicians keep having this debate is thanks to ongoing debt issuance by our government in order to fund bailouts during downturns as well as government outlays that exceed government revenues. All this debt climbs on top of that massive $28+ trillion pile of public debt.

The U.S. Debt Clock (Source).

However, at some point, even powerful governments feel the heat from angsty lenders and need a new set of tools. Throughout history, governments in a corner have employed another tool to service their debt and continue to prolong the debt cycle: debt monetization. The U.S. government opened this toolbox in 1971 by disconnecting the U.S. dollar — and all global currencies — from gold thus creating the fiat currency system we still live with today.

Fiat currency, like that friend who only calls when he needs something, shows up often in history but never stays for long. “Fiat” roughly translates from Latin as “by decree.” Fiat currency is thus money which derives its use — and value — by decree from a governing body. Fiat currency is not hard money; the governing body often (solely) reserves the right to create the currency and distribute it through some mechanism.

In a fiat currency system where depositors are placing fiat currency into banks, we have a new trick for unwinding debts.

Remember how bad times in the debt cycle led to the bank having more claims against their assets than assets on their books? Within a fiat currency system, the governing body can now solve this little ledger problem by just creating more currency. Poof, everyone gets paid.

We call this tool for ending debt cycles monetization, because we “monetize” the debts by paying them with newly created currency.

Today, we often call these governing bodies that create currency “central banks,” and together with their partners in government we believe these entities are capable of “softening” the frequent crashes endemic to an economy with any kind of lending. We like lending, because when it goes well, everyone benefits, so this fiat currency system appears to be a decent way of easing the pain of downturns.

The Effect Of Monetizing Debt

We already know that paying down debts costs the borrower, whereas defaulting on them costs the lender. Many central bankers and politicians would like to drown you in jargon at this point, leaving you with the impression that monetization solves the painful dilemma of pay or default, even if they can’t articulate just how.

So who foots the bill when we monetize debts?

When debts are monetized, new currency enters circulation, diluting the value of all the existing currency in circulation. This dilution of value of new currency is felt through inflation, which we’re hearing a lot about lately.

Those citizens who work on a fixed salary or wage and keep most of their net worth in the currency suffer from inflation the most, while those closest to the government and banking system with most of their net worth in non-cash assets benefit. It is those former citizens, the ones furthest away from the currency “spigot” and least aware of the effects of inflation, who pay for debt monetization.

The endgame of debt monetization is hyperinflation, which occurs when the central bank decides to go bananas and print, print, print to pay down every debt. Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and pre-WWII Germany come to mind. This is not a pretty event for anyone involved. Unlike defaulting or paying down debt, where effects are contained to the lenders and borrowers involved, monetization leads down a road ending in not just economic collapse but societal collapse.

The cost of one kilogram of tomatoes in Venezuelan bolivars in 2018 (Source).

Monetizing debt has serious costs, so operators of fiat currency systems must act cautiously. However, monetizing debt throughout history has often been more politically favorable than paying or defaulting, likely owing to the fact that it’s harder for people to understand who is footing the bill.

Governments And The Never-Ending Debt Cycle

Now that we understand how fiat currency enables debt monetization, let’s jump back to governments and their giant debt piles.

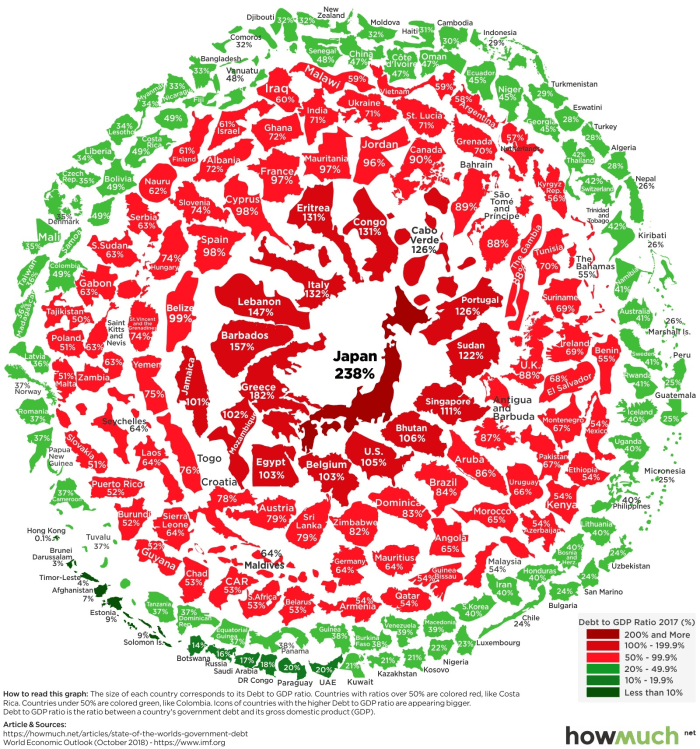

The government debt to national GDP ratios of every nation in the world, pre-COVID (Source).

As a government’s pile of debt grows, it becomes ever more difficult and painful to pay it down, default on it or monetize it. Nobody from the politician to the politically connected elite to the welfare recipient wants budget cuts in their area, especially in the name of paying down the public debt. Defaulting would mean lenders would lose confidence in the government, demanding higher interest rates in order to make further loans thus forcing budget cuts. Debt monetization, taken too far, rips apart the fabric of society.

This results in an increasing desperation by the government to keep the status quo intact. Just keep the debt growing and push the problem onto the next generation.

The free market can bring an end to this debt cycle by simply “shorting” (selling) government bonds (loan contracts), making it more expensive for the government to borrow. However, a fiat currency system makes this difficult, because the central bank can print unlimited fiat currency and use it to buy bonds. Since the central bank incurs no cost to print currency, they are the ultimate player in the market. An investor who sells government bonds is destined to lose to a central bank that will never stop buying, so most investors go along with the game. This destroys the free market’s ability to bring an end to overborrowing.

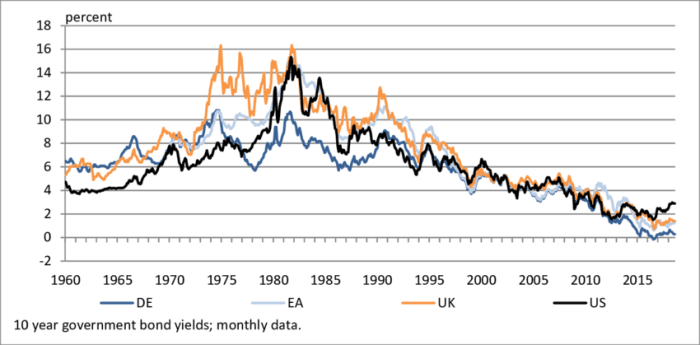

Central banks for the past 50 years have proven to us, unequivocally, that they will support their governments’ borrowing habits and fight off the free market that would keep the debt cycle in check.

Interest rates for major government bonds have trended down since the early 1980s, following the birth of a global fiat monetary system in 1971 (Source).

When central banks buy government bonds, they pay for them with newly printed currency. This is what I mean by monetizing debt. Too much of this, and we get the hyperinflation scenario we all want to avoid.

As debts climb, all options — from paying and defaulting to monetizing — become more and more painful. So what is a government to do in order to continue lengthening the debt cycle?

We’re Doing This For Your Own Good

Continuing the borrowing bonanza without an unwinding force by the free market requires governments to employ tools of a more authoritarian or subversive variety. The United States has a long and well-hidden history of these tactics, from seizing the gold of its citizens in the 1930s to partnering with oil-rich despots in the 1970s to issuing jargon-clad explanations for quantitative easing during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

Monetary debasement is the powerful government’s tool of choice to forego the inevitable, but sustaining that tool’s power requires preventing free individuals from forcing a return to rationality. As public debt rises, governments will consider new measures to kick the can such as:

Raising revenue through increased taxation like unrealized capital gains.More intense financial surveillance and controls to stabilize the currency’s value. Legal workarounds to mint trillion dollar coins to further dilute the currency supply and “monetize” the problem of excessive government spending.

As long as governments like the United States continue to overspend, bailing out every short-term debt cycle, they will simply delay paying the bills and either increase the severity of an eventual unwinding — via payments or default — or trigger a collapse of society through debt monetization. We will all pay for a century of foregone debts through some combination of increased taxation, inflation and loss of freedom.

Waking Up

When will we wake up and see this system for what it is? Unfortunately, most probably never will. They will blame immigrants or billionaires, depending on their political bent, for the ills of our time. They will continue to defend the system, even as the tightness of its controls and severity of its punishments increase.

“Many of them are so inured and so hopelessly dependent on the system that they will fight to protect it,” (Source).

This knowledge is your power. Now that you see the trajectory of the long-term debt cycle, what steps will you take to bring a better future?

The realizations I’ve written here are the reasons I buy, hold and support Bitcoin — an accessible form of hard money that can support a modern, digital and global economy. Bitcoin is a lifeline extending to a world where debt cycles are kept short and crashes are contained, where governments are robbed of a critical tool for lengthening the end of the debt cycle into a societal collapse. Supporting Bitcoin forces governments to be rational yet again, to balance their budgets and pay down debts, to avoid monetization.

Will you be part of the solution or part of the perpetuation?

This is a guest post by Captain Sidd. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.

Source link

#Debt #Ceiling #Cliff #Raising